Vijayarama (Sinhala: විජයාරාම නටඹුන්) is a ruined Buddhist monastery site situated in Anuradhapura District, Sri Lanka.

History

Vijayarama is considered a monastery that had connections to Mahayana Buddhism

(Jayasuriya, 2016; Prematilleke & Silva, 1968). Several copper

plaques containing a portion of the Sutra called Prajna Paramita

or invocations to Mahayana deities such as Avalokitesvara, Tara, and

Akasagarbha have been found from the Stupa of this site (Prematilleke

& Silva, 1968; Wikramagamage, 2004). These plaques have been dated to the 9th century A.D. (Dhammaratana, 2000).

Monastery complex

Vijayarama is a monastery of the Pabbatha Vihara (rock monasteries or mountain temples) type (Jayasuriya, 2016; Prematilleke & Silva, 1968).

Asokaramaya, Pacinatissa-pabbata Viharaya, Puliyankulama Purvarama, and

Toluvila are several other monasteries that have features similar to

Vijayarama monastery (Jayasuriya, 2016; Prematilleke & Silva, 1968).

A large central terrace (known as the sacred quadrangle) of about 288 feet long and 268 feet wide with the ruins of four edifices namely, the Stupa, Bodhighara (the Bodhi-tree shrine), Patimaghara (the image house), and Uposathaghara (the chapter house) are found at the site (Jayasuriya, 2016; Prematilleke & Silva, 1968). These four edifices, together with the Sabha building at the centre of the terrace constitute the Pancavasa as described in the Silpa text Manjusri-Vastuvidya-Sastra (Jayasuriya, 2016).

The central terrace of Vijayarama can be approached through four porches facing the cardinal points. Each porch is said to be accompanied by the figures of four animals; elephant (the east porch), horse (the south porch), lion (the north porch) and bull (the west porch). The Muragal (the guard-stones) flanking the flights of steps of the southern and western entrances of the terrace are carved with the figure of a dwarf (Prematilleke & Silva, 1968). Several bronzes including the statues of directional deities (dikpala), viz., Indra (east), Yama (south), Varuna (west), Kuvera (north) were recovered from cellas underneath the four entrance porches of the terrace (Prematilleke & Silva, 1968). Besides that, more artefacts of the 9-10th century A.D. such as lamps, stone containers have also been discovered from the site (Ślączka, 2007).

A moat can be seen around this central terrace. The space between the central terrace and the moat is called the lower platform. The ruins of other ancient buildings such as Jantaghara (the monks' bath-house), Refectory, and monks' cells have been discovered outside of the central terrace (Jayasuriya, 2016).

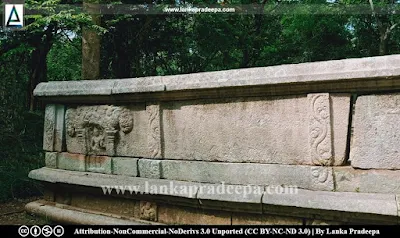

The human figures of the plinth of the projecting open terrace at the Vijayarama;

The central terrace of Vijayarama can be approached through four porches facing the cardinal points. Each porch is said to be accompanied by the figures of four animals; elephant (the east porch), horse (the south porch), lion (the north porch) and bull (the west porch). The Muragal (the guard-stones) flanking the flights of steps of the southern and western entrances of the terrace are carved with the figure of a dwarf (Prematilleke & Silva, 1968). Several bronzes including the statues of directional deities (dikpala), viz., Indra (east), Yama (south), Varuna (west), Kuvera (north) were recovered from cellas underneath the four entrance porches of the terrace (Prematilleke & Silva, 1968). Besides that, more artefacts of the 9-10th century A.D. such as lamps, stone containers have also been discovered from the site (Ślączka, 2007).

A moat can be seen around this central terrace. The space between the central terrace and the moat is called the lower platform. The ruins of other ancient buildings such as Jantaghara (the monks' bath-house), Refectory, and monks' cells have been discovered outside of the central terrace (Jayasuriya, 2016).

The human figures of the plinth of the projecting open terrace at the Vijayarama;

The most attractive feature of this fine piece of work are the carved stones decorating the exterior wall of the platform. These are panels with figures differing from each other, some containing only a single male figure and others a male and female. They stand beneath a carved canopy of curious makara - pattern. These bloated dragon beasts face each other open-mouthed, each with a figure, sometimes human, sometimes animal, in their jaws. In the hollows of their backs are quaint dwarfs. The makaras, with their curved backs and fish-like tails, here much more resemble dolphins than crocodiles. Besides these there are striking gargoyles and bits of floral decoration falling vertically.Citation: Mitton, 1917.pp.137-138.

Prematilleke and Silva believe that these human figures represent deities (Prematilleke & Silva, 1968). According to them, the single male figures may represent Naga kings while the couples (male and female) represent either Siva or Visnu with Sakti (Prematilleke & Silva, 1968).

Vijayarama copper plaques

Revealing the evidence for the Mahayana affiliation, thirteen copper plaques with epigraphs of invocations to Mahayana Buddhas and Bodhisattvas (such as Sikhi Buddha, Gagana Buddha, Akasa Garbha Bodhisattva, Tara etc.) were discovered from the Stupa of Vijayarama (Dhammaratana, 2000). They were in the relic chamber of the Stupa that, at the time of the discovery, had been ransacked by thieves (Dhammaratana, 2000).

The epigraphs have been composed in the Sinhala scripts of the 9th century, the period when Mahayana Buddhism had flourished around Sri Lanka (Dhammaratana, 2000). Except for the first one which has a stanza written in the Pali language, the other plaques contain invocations in the Sanskrit language (Dhammaratana, 2000). These invocations may have been engraved on the copper plaques as a form of religious worship and for invoking blessings (Dhammaratana, 2000).

The epigraphs have been composed in the Sinhala scripts of the 9th century, the period when Mahayana Buddhism had flourished around Sri Lanka (Dhammaratana, 2000). Except for the first one which has a stanza written in the Pali language, the other plaques contain invocations in the Sanskrit language (Dhammaratana, 2000). These invocations may have been engraved on the copper plaques as a form of religious worship and for invoking blessings (Dhammaratana, 2000).

.

.

References

1) Dhammaratana, I., 2000. Sanskrit Inscriptions in Sri Lanka: A thesis

submitted to the University of Pune in partial fulfillment of the

requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sanskrit.

Department of Sanskrit & Prakrit Languages, University of Pune,

India. pp.364-373.

2) Jayasuriya, E., 2016. A guide to the Cultural Triangle of Sri Lanka. Central Cultural Fund. ISBN: 978-955-613-312-7. p.57.

3) Mitton, G.E., 1917. The lost cities of Ceylon. FA Stokes Company. pp.137-138.

4) Prematilleke, L. and Silva, R., 1968. A Buddhist Monastery Type of Ancient Ceylon Showing Mahāyānist Influence. Artibus Asiae, pp.61-84.

5) Ślączka, A.A., 2007. Temple consecration rituals in Ancient India: text and archaeology (Vol. 26). Brill. pp.370-371.

6) Wikramagamage, C., 2004. Heritage of Rajarata: Major natural, cultural,

and historic sites. Colombo. Central Bank of Sri Lanka. p.112.

Location Map

This page was last updated on 6 September 2022