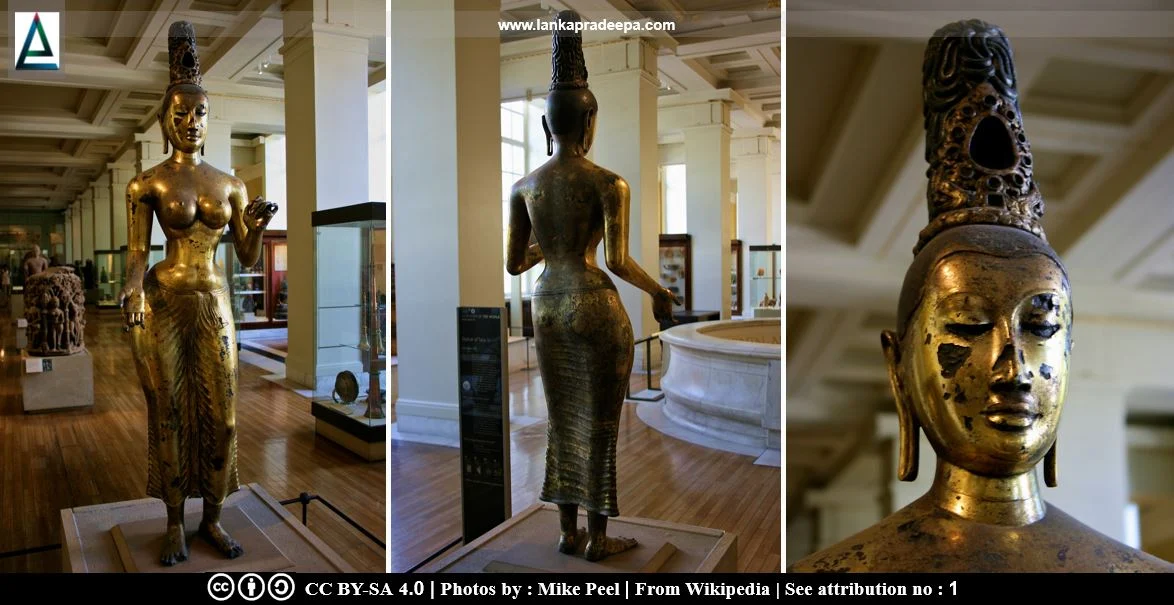

The Statue of Tara Devi (Sinhala: තාරා දේවි ප්රථිමාව, බ්රිතාන්ය කෞතුකාගාරය; Tamil: தாரா சிலை) is an 8th-century gilt-bronze sculpture of the goddess Tara discovered in Sri Lanka. Presently, it is on the display at the British Museum, United Kingdom.

The Statue of Tara Devi (Sinhala: තාරා දේවි ප්රථිමාව, බ්රිතාන්ය කෞතුකාගාරය; Tamil: தாரா சிலை) is an 8th-century gilt-bronze sculpture of the goddess Tara discovered in Sri Lanka. Presently, it is on the display at the British Museum, United Kingdom.Statue of Tara from the British Museum

Museum number : 1830,0612.4

Cultures / periods: Buddhist / Anuradhapura

Production date : 8th-century A.D. (circa)

Production place : Sri Lanka

Materials : Bronze, gold

Technique : gilded cast

Dimensions : Height: 143 cm (not including plinth)

Width : 44 cm

Depth : 29.50 cm

Exhibition history: 1. 'The Art of Ancient Sri Lanka': exhibition at the Commonwealth Institute, London (17 Jul to 13 Sep 1981)

2.'Buddhism: Art and Faith': temporary exhibition at the British Museum, London (1985)

3. 'A History of the World in 100 Objects', London, BM/BBC (2010-2011)

Subjects : Bodhisattva deity

Associated names: Tārā

Reference : British Museum Collection (1830,0612.4)

To the British Museum

The statue was handed over to the British Museum in 1830 by Brownrigg or by his wife (Dohanian 1983; Jayawardene, 2016). In the 1980s, she was accorded pride of place in the museum's South Asia Gallery (Jayawardene, 2016).

The statue was handed over to the British Museum in 1830 by Brownrigg or by his wife (Dohanian 1983; Jayawardene, 2016). In the 1980s, she was accorded pride of place in the museum's South Asia Gallery (Jayawardene, 2016).

Tara Devi is considered the most beloved goddess of the Mahayana Buddhist pantheon (Jayawardene, 2016). She started to appear in the society of Sri Lanka around the seventh or eighth century A.D. and was worshipped until the fifteenth century A.D. (Jayawardene, 2016). Evidence for Tara worship in Sri Lanka is found in the Mihintale Slab Inscriptions of Mahinda IV (956-972 A.D.) where she is referred to as goddess Mininal (Gunawardana, 2019; Jayawardene, 2016; Wickremasinghe, 1912). The largest figure of Tara in the country is found in Buduruwagala (Gunawardana, 2019).

The statue

This solid-cast, gilt bronze statue of Tara Devi is 1.43 m tall and is in the Abhanga pose (Jayawardene, 2016). It has a Jatamakuta (a high tubular coiffure) held in place by Makaras. It had been garnished with stones but they are no more available. The empty niche in the front of the Jatamakuta would have contained a small seated image of the Buddha. The upper body is completely naked and the lower body is dressed with a flimsy cloth (antariya) tightly knotted at the hips. The waist is small and the breasts are round. The lowered right hand is in the Varada Mudra while the raised left hand is in the Katakahasta Mudra (Dohanian 1983; Gunawardana, 2019; Jayawardene, 2016). The two middle fingers of the right hand are missing as are toes from both feet.

Some scholars had misunderstood this statue, to be the statue of the goddess Pattini (Coomaraswamy, 1909; Gunawardana, 2019). However, it is now identified as a statue of Tara. It probably stood inside a temple, with her male consort, Avalokiteshvara, but his image has not survived. Scholars have dated this statue to about the 8th century A.D. of the Anuradhapura Period (Dohanian 1983; Gunawardana, 2019; Jayawardene, 2016).

A looted statue?

Discovery

The findspot of the statue is not certainly known (Jayawardene, 2016). However, it is said to have been found from somewhere on the east coast of the country between Batticaloa and Trincomalee (Gunawardana, 2019).

The statue was removed from Ceylon (present Sri Lanka) in 1820 by the then Governor of Ceylon, Sir Robert Brownrigg (Jayawardene, 2016). Brownrigg was a soldier and he was made a Baronet in 1816 and a General in 1819 in recognition of his conquest of Sri Lanka's last kingdom, the Kandyan Kingdom in 1815 which resulted in the subjugation of the entire island to British rule (Jayawardene, 2016). It is supposed that Brownrigg uncovered the statue on the country's eastern coast and subsequently brought it to Britain (Howland et al., 2016). However, according to Sri Lankan officials, it had been wrongfully seized by Brownrigg from the collection of the last king of Kandy, Sri Vikrama Rajasinghe [(1798-1815 A.D.) Howland et al., 2016].

The statue was handed over to the British Museum in 1830 by Brownrigg or by his wife (Dohanian 1983; Jayawardene, 2016). In the 1980s, she was accorded pride of place in the museum's South Asia Gallery (Jayawardene, 2016).

The statue was handed over to the British Museum in 1830 by Brownrigg or by his wife (Dohanian 1983; Jayawardene, 2016). In the 1980s, she was accorded pride of place in the museum's South Asia Gallery (Jayawardene, 2016).Repatriation Denied

Despite the 1970 UNESCO and 1995 UNIDROIT Conventions, attempts to repatriate objects plundered in centuries past have frequently failed (Howland et al., 2016). The statue of Tara Devi is an example of one such object (Greenfield, 1996; Howland et al., 2016).

Sri Lankan authorities identify this statue as a treasure removed from their country (Howland et al., 2016). In 1937, the Government of Ceylon under British rule made an official request to the British Museum to return the statue back to its original country but it was denied (Jayawardene, 2016). In 1980, the Sri Lankan Government made an official approach to the British Government for the return of specific objects in their museums (Greenfield, 1996). However, it became fruitless when the British Government refused to hand over them in 1981 (Greenfield, 1996).

A replica for Sri Lanka

.

A replica for Sri Lanka

A plaster cast of the statue was donated later to the Colombo National Museum by the British Museum (Jayawardene, 2016). In 2004, the cast was replaced by a bronze statue (Jayawardene, 2016). Today this replica is being displayed at the Anuradhapura Gallery of Colombo Museum.

Watercolour painting

Tara statue was illustrated in the watercolour painting produced by the artist James Stephanoff (1788-1874) in 1845. His painting ordered artefacts from known civilizations into an elitist hierarchy based on the perception of their aesthetic importance.

.

Attribution

1) Statue of Tara, British Museum 4, Statue of Tara, British Museum 2, & Statue of Tara, British Museum 3 by Mike Peel are licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

References

1) Coomaraswamy, A.K., 1909. Mahayana Buddhist images from Ceylon and Java. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 41(2), pp.283-297.

2) Dohanian, D.K., 1983. Sinhalese Sculptures in the Pallava Style. Archives of Asian Art, 36, pp.6-21.

3) Greenfield, J., 1996. The return of cultural treasures. Cambridge University Press. pp.131-132.

4) Gunawardana, N., 2019. Identify the statues of Goddess Tārā in Sri Lanka and Evaluate the Importance with Trade. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, 9(9), pp.404-410.

5) Howland, D., Lillehoj, E. and Mayer, M. eds., 2016. Art and Sovereignty in Global Politics. Springer. pp.148-149

6) Jayawardene, S., 2016. Sri Lanka's Tārā Devī. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Sri Lanka, 61(2), pp.1-30.

7) Wickremasinghe, D.M.D.Z., 1912. Epigraphia Zeylanica: Being lithic and other inscription of Ceylon (Vol. I). London. Archaeological Survey of Ceylon. p.103.

Location Map

This page was last updated on 8 January 2023