Sigiriya (Sinhala: සීගිරිය; Tamil: சிகிரியா) is an ancient fortress built on the summit of a rock [363 m (1,190.94 ft. amsl)] situated in Matale District, Sri Lanka. The fortress is today a recognized World Heritage Site and is popularly known among the people as the eighth wonder of the World.

World Heritage Site: Ancient City of Sigiriya

Location: Matale District, Central Province, Sri Lanka

Coordinates: N7 57 0 E80 45 0

Date of Inscription: 1982

Description: The ruins of the capital built by the parricidal King Kassapa I (477–95) lie on steep slopes and at the summit of a granite peak standing some 180m high (the 'Lion's Rock', which dominates the jungle from all sides). A series of galleries and staircases emerging from the mouth of a gigantic lion constructed of bricks and plaster provide access to the site.

Criteria: (ii) exhibit an important interchange of human values, over a span of time or within a cultural area of the world, on developments in architecture or technology, monumental arts, town-planning or landscape design.

(iii) bear a unique or at least exceptional testimony to a cultural tradition or to a civilization which is living or which has disappeared.

(iv) an outstanding example of a type of building, architectural or technological ensemble or landscape which illustrates (a) significant stage(s) in human history.

Reference: 202; Ancient City of Sigiriya, UNESCO World Heritage Centre, United Nations.

History

The history of Sigiriya goes back to very early times. The drip-ledged caves with pre-Christian Brahmi Inscriptions indicate that the Sigiriya was an abode of forest-dwelling Buddhist monks since the pre-Christian era (Chutiwongs et al., 1990; Paranavitana, 1970).

King Datusena & Prince Kassapa

King Kassapa (477-495 A.D.), one of the two sons of King Datusena (463-477 A.D.), converted this unscaleable Sigiriya rock into a marvellous fortress and built a planned city around it (Chutiwongs et al., 1990; Devendra, 1951; Ray, 1959). According to the chronicles such as Mahavamsa, Datusena who was ruling the island from Anuradhapura had two sons, a daughter, a sister and her son (Devendra, 1951). Prince Kassapa, one of two sons of Datusena, was born of a lady, not of queenly rank and therefore, he had no claim to the throne but Prince Moggallana, the other son was born to a main queen becoming the rightful heir to the throne (Devendra, 1951). Datusena's daughter was married to the sister's son who was Commander-in-Chief and on one occasion she complained to her father that her husband whipped her on the thigh (Devendra, 1951). After hearing that, Datusena lost control of himself and he killed his sister or the mother-in-law of his daughter by stripping and burning her alive (Devendra, 1951). Her son Commander-in-Chief took revenge for this by assisting Datusena's son Prince Kassapa to usurp the throne who finally imprisoned his father and later put him to death by walling in a dungeon (Devendra, 1951). Meanwhile, the other son of Datusena, Prince Moggallana escaped to India for help against the usurper and his supporters (Ray, 1959).

Construction of Sigiriya Fortress

In fear of his escaped brother Moggallana, King Kassapa sought security in the rock of Sigiriya and transformed it into an impregnable fortress (Devendra, 1951). He built his abode on the summit of the rock which according to the chronicle was a palace-like unto a second Alakamanda, the abode of God Kuvera, the lord of wealth (Nicholas, 1963). Kassapa named his fort as Sinha-giri (Lion-rock) and turned the nearby Pidurangala into a shrine of religious worship.

The Sinha-giri rock was the central feature of Kassapa's fortress. The enclosing ramparts on two sides of it formed two cities on the east and the west (Devendra, 1951).

End of the Kassapa era

Kassapa proudly ruled the country for nearly two decades until his brother Moggallana came back with a powerful army from India. On the battlefield, Kassapa had to turn his elephant back to find a way to skip a swamp in front of him but his men mistook it for a sign that their master was going to flee (Devendra, 1951). The discouraged army dispersed finally compelling Kassapa to admit defeat and commit suicide on the field (Devendra, 1951).

Moggallana became the king and ruled the island from the City of Anuradhapura from 495 to 512 A.D. He handed over the rock of Sigiriya to the monks of Dharmarucikas who followed the Mahayanist form of Buddhism under the Abhayagiriya Sect (Chutiwongs et al., 1990).

The name of Sigiriya is mentioned in chronicle Mahawamsa again at the beginning and end of the 7th century. It accounts that there were two occasions of further killings of royalty at Sigiriya in Samghathissa II and Moggallana III (Chutiwongs et al., 1990). Thereafter the name Sigiriya does not occur in any of the local chronicles (Chutiwongs et al., 1990).

The Boulder Arch No. 01 (right photograph)

The Boulder Arch No. 01 (right photograph)Description: The Boulder Arch No. 01 which is on the ancient pathway shows the successful adoption of features of the natural landscape in Sigiriya planning. Two caves prepared as dwellings for the Buddhist monks during the first monastic phase before Kassapa are visible on either side of the arch.

The inscription (in the left cave)

Period: 3-1 century B.C.

Script: Early Brahmi

Language: Old Sinhalese

Transcript: Parumaka Kadiya puthasha...

Translation: (the cave of) chieftain Kadiya's son

Reference: Paranavitana, 1970. p.67.

Bodhi and Uppalavanna? (left photograph)

Bodhi and Uppalavanna? (left photograph)

Naipena Guhava/B 9 Cave (right photograph)

Naipena Guhava/B 9 Cave (right photograph)

The Cobra Hood cave inscription

Period: 3-1 century B.C.

Script: Early Brahmi

Script: Early Brahmi

Language: Old Sinhalese

Transcript: Parumaka Kadiya puthasha...

Translation: (the cave of) chieftain Kadiya's son

Reference: Paranavitana, 1970. p.67.

Rediscovery

Sigiriya was rediscovered by Forbes in April 1831 and was scaled in 1853 by Adams and Bailey (Chutiwongs et al., 1990).

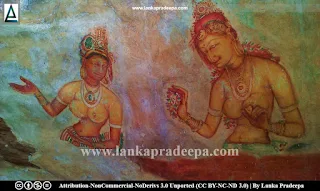

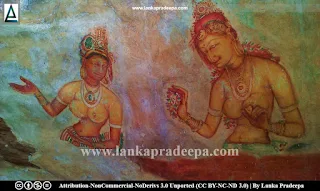

Paintings

Sigiriya is a secular monument with fine paintings of the classical era (Chutiwongs et al., 1990). The paintings are found on the western face of the rock boulder and in the sheltering caves of the surrounding garden. The major group of paintings is in the pockets on the western face of the rock. There are five figures of damsels in pocket A and eighteen in pocket B making a total of twenty-three figures (Chutiwongs et al., 1990). The damsel figures are depicted as rising from clouds hence the lower part of the body below the waist is not visible. These are the oldest and best-preserved paintings in Sigiriya dated to the 5th century A.D. (Paranavitana, 1950).

Bodhi and Uppalavanna? (left photograph)

Bodhi and Uppalavanna? (left photograph)

The chronicle Mahawamsa says that King Kassapa restored the Issarasamana Vihara (modern Vessagiriya) and renamed it as Bo-Upulvan Kasubgiri Vihara, giving it his own name and the names of his two favourite daughters Bodhi (light) and Uppalavanna (blue-lily complexioned). The pair of light-complexioned and dark-hued ladies in this painting, according to the view of Chutiwongs et al., could therefore represent the two royal princesses (Chutiwongs et al, 1990).

More paintings are found on the rock ceilings of the Deraniyagala cave (cave no. 7), Asana cave and Naipena Guhava (Cobra-hood cave) in the surrounding garden (Chutiwongs et al., 1990). The Deraniyagala cave contains several fragments of paintings belonging to the late 6th century A.D. (Chutiwongs et al., 1990)

The paintings found in the Naipena Guhava, dated to the late 6th and early 7th centuries, are mainly decorative motifs of medallions and bands which are similar in the theme and style to those found in the caves at Ajantha in India (Chutiwongs et al., 1990).

Naipena Guhava/B 9 Cave (right photograph)

Naipena Guhava/B 9 Cave (right photograph)Description: Naipena Guhava (the Cobra Hood Cave) is a cave with drip ledges that had been used as a dwelling for Buddhist monks during the first monastic phase before Kassapa. Nine skeletons have been recovered during an excavation carried out in front of the cave.

The Cobra Hood cave inscription

Period: 3-1 century B.C.

Script: Early Brahmi

Language: Old Sinhalese

Transcript: Parumaka-Naguliya lene

Translation: The cave of the chief Naguli (Langali)

Reference: Paranavitana, 1970. p.67.

Vandalism

.

2) Sigiriya boulder gardens 21 by Cherubino is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Transcript: Parumaka-Naguliya lene

Translation: The cave of the chief Naguli (Langali)

Reference: Paranavitana, 1970. p.67.

The Paintings in the Asana Guhava located nearby belong to the 12th century AD. There is a seat (Asana) inside the cave, carved out of the living rock. A few pieces of graffiti belonging to the 8-9 centuries AD have been found in the cave.

Vandalism

On the night of 14th October 1967, a commercial paint had been daubed on fourteen of the nineteen paintings in pockets A and B (Wijesekara, 1990). Two figures had also been damaged by hacking away the head of one figure and the portion above the waist of the other figure (Wijesekara, 1990).

Graffiti on the Mirror Wall

Visitors who came to Sigiriya from the 7th to the 19th century have left their comments on the wall presently known as Kedapat-pavura or Mirror Wall. The surface of it originally had been white and the people who visited the site used fine points of metal to cut the surface to engrave their comments (Devendra, 1951). The comments belonging to the 6th and 13th centuries are known as Sigiri graffiti and they describe the beauty of the damsels painted on the rock surface as well as the surrounding environment of the royal park.

.

See also

Attribution

1) Sigiriya boulder gardens 05 by Cherubino is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.02) Sigiriya boulder gardens 21 by Cherubino is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

References

1) Chutiwongs, N., Prematilleke, L., Silva, R., 1990. Paintings of Sri Lanka: Sigiriya: Colombo, Archaeological Survey of Sri Lanka, Centenary Publications, Central Cultural Fund. pp. 37-47.

2) Devendra, D. T., 1951. Guide to Sigiriya. Ceylon Government Press. pp.2-27.

2) Devendra, D. T., 1951. Guide to Sigiriya. Ceylon Government Press. pp.2-27.

3) Nicholas, C. W., 1963. Historical topography of ancient and medieval Ceylon. Journal of the Ceylon Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, New Series (Vol VI). Special Number: Colombo. Royal Asiatic Society (Ceylon Branch). p.110.

4) Paranavitana, S., 1950. Sinhalese Art and Culture. Journal of the Royal Society of Arts, 98(4822), pp.588-605.

5) Paranavitana, S., 1970. Inscription of Ceylon: Volume I: Early Brahmi inscriptions. Department of Archaeology Ceylon. p.67.

6) Ray, H. C. (Editor in chief), 1959. University of Ceylon: History of Ceylon. Vol 1. Part I. Ceylon University Press. pp.296-298.

7) Wijesekara, N., Silva, R. D., 1990. Archaeological Department Centenary (1890-1990): Commemorative Series (Vol. V). Painting: Colombo. Commissioner of Archaeology. p.19.

Explore Other Nearby Attractions

Location Map (Google)

This page was last updated on 22 July 2023