Rangiri Dambulla Cave Temple, also known as Dambulu Raja Maha Viharaya, Golden rock temple of Dambulla or Cave temple of infinite Buddhas (Sinhala: දඹුල්ල රජමහා විහාරය; Tamil: தம்புள்ளை பொற்கோவில்), is an ancient Buddhist temple located in Dambulla in Matale District, Sri Lanka. It is considered the largest, best-preserved cave-temple complex in the country as well as the second-largest cave-temple complex in South and Southeast Asia (State of Conservation Report, 2019). Presently, UNESCO has declared this site as one of the World Heritage Sites in Sri Lanka.

World Heritage Site: Rangiri Dambulla Cave Temple

Location : Matale District, Central Province, Sri Lanka

Coordinates : N7 51 24 E80 38 57

Date of Inscription : 1991

Criteria : (i) The monastic ensemble of Dambulla is an outstanding example of the religious art and expression of Sri Lanka and South and Southeast Asia. The cave shrine, their painted surfaces, and statuary are unique in scale and degree of preservation. The monastery includes significant masterpieces of 18th-century art in the Sri Lankan school of Kandy.

(vi) Dambulla is an important shrine in the Buddhist religion in Sri Lanka, remarkable for its association with the long-standing and widespread tradition of living Buddhist ritual practices and pilgrimage for more than two millennia.

Reference : 561: Rangiri Dambulla Cave Temple, UNESCO World Heritage Centre, United Nations.

History

Pre & protohistoric periods

Evidence regarding prehistoric man has been identified along the western slope of the Dambulla rock where a series of large boulders, terraces, and caves can be seen (Jayasuriya, 2016; State of Conservation Report, 2019). Several prehistoric stone implements have been found during the excavations done on the uppermost terrace of the Dambulla complex (State of Conservation Report, 2019).

The prehistoric period was succeeded by the protohistoric period at some time during the first millennium B.C. The Megalithic Tombs at Ibbankatuwa, a protohistoric burial site located about 3 km to the southwest of Dambulla, contains evidence that reveals probable connections between the burial site and the Dambulla complex during the protohistoric period (Bandaranayake, 1997; Jayasuriya, 2016; State of Conservation Report, 2019).

Evidence regarding prehistoric man has been identified along the western slope of the Dambulla rock where a series of large boulders, terraces, and caves can be seen (Jayasuriya, 2016; State of Conservation Report, 2019). Several prehistoric stone implements have been found during the excavations done on the uppermost terrace of the Dambulla complex (State of Conservation Report, 2019).

The prehistoric period was succeeded by the protohistoric period at some time during the first millennium B.C. The Megalithic Tombs at Ibbankatuwa, a protohistoric burial site located about 3 km to the southwest of Dambulla, contains evidence that reveals probable connections between the burial site and the Dambulla complex during the protohistoric period (Bandaranayake, 1997; Jayasuriya, 2016; State of Conservation Report, 2019).

Early-historical period

The early-historic period of Sri Lanka began at some time around the 3rd century B.C. The archaeological evidence that belongs to the early-historic period has been found in the Dambulla complex (Bandaranayake, 1997). The site contains nearly 90 drip-ledged cave shelters prepared for the usage of Buddhist monks (State of Conservation Report, 2019). Some of them contain Early Brahmi Inscriptions engraved just below the drip ledge (Paranavitana, 1970; Seneviratna, 1983). Presently, about 37 cave inscriptions belonging to the period between the 3rd century B.C. and the 2nd century A.D. have been found in association with these drip-ledged rock shelters (State of Conservation Report, 2019).

Although the fact is not exactly proven, popular oral tradition as well as several chronicles such as Pujavaliya, Rajavaliya and Rajaratnakara (a work of the 18th century) mention that this temple was established by King Valagamba (103, 89-77 B.C) during the 1st century A.D. (Seneviratna, 1983; State of Conservation Report, 2019). Two early Brahmi inscriptions discovered from the Dambulla complex contain the names of two royals: Devanampiya Maharaja Gamini Tissa and Gamini Abhaya (Seneviratna, 1983). According to the view of some scholars such as S Paranavitana, the first name may refer to King Devanampiyatissa (247-207 B.C.) or King Saddhatissa (137-119 B.C.) while the second name refers to King Valagamba (Abeyawardana, 2004; Seneviratna, 1983).

There is an inscription of the first century A.D. engraved on the rock wall of a cave located on the hillside to the west of the Dambulla rock (Seneviratna, 1983). It records the construction of a Stupa named Catavanaceta (Catavana Chetiya) and a donation made to it by a Thera named Sedadeva (Seneviratna, 1983). Some have assumed that the Catavana Chetiya of this inscription may be the Stupa presently known as Somawathi Stupa (Seneviratna, 1983). Besides the inscriptions in the caves, a number of epigraphs belonging to the 1st-4th centuries A.D. have been discovered on the rock-cut steps of the pilgrim pathway that leads to the cave temple (State of Conservation Report, 2019).

Middle-historical period

During the period between the 5th to 13th centuries A.D., many changes were made to the temple by its patrons (Jayasuriya, 2016). The temple was further developed by adding new components to it and the caves were transformed into cave shrines elaborated with screen walls, paintings, and sculptures. Several painting fragments that were found below the drip-ledge of Cave Shrine 3 have been dated to a period between the 5th to 7th centuries A.D. (State of Conservation Report, 2019). The archaeological investigations carried out at the base on the western side of the Dambulla rock during the 1980s and the 1990s identified the ruins of the Somawathi Stupa monastery that belongs to two periods of construction [(5th to 6th centuries A.D. and 9th to 10th centuries A.D.) State of Conservation Report, 2019].

During the 11th and 12th centuries A.D., the temple received the royal patronage of the Polonnaruwa kings. The chronicle Culavamsa (also known as the latter part of Mahavamsa) refers to this temple for the first time as Jambukola Viharaya (the Sinhala name Dambulla is believed to have been translated into Pali as Jambukola by the author of this chronicle) in the reign of King Vijayabahu I [(1055-1110 A.D.) Jayasuriya, 2016; Seneviratna, 1983]. It reveals that Vijayabahu I had renovated the temple (Abeyawardana, 2004; State of Conservation Report, 2019). According to the details found in several chronicles (such as Mahavamsa, Pujavaliya) and the inscription (See: Dambulla Rock Inscription of Kirti Nissankamalla) on the rock face of the Cave Shrine 1, King Nissankamalla (1187-1196 A.D.) has commissioned the sculpture in the Cave shrine 1 (the Devarajalena), refurbished the existing cave shrines, overlaid 73 Buddha statues with gold and renamed it "Svarnagiri-guha" [(the golden rock cave) Abeyawardana, 2004; Jayasuriya, 2016; Seneviratna, 1983; State of Conservation Report, 2019; Wickremasinghe, 1912]. The Pritidanamandapa inscription and Galpota Inscription at the Polonnaruwa Ancient City also confirm Nissankamalla's activities at the Dambulla Viharaya (Seneviratna, 1983).

Late-historical period

After the 13th century, many kings such as Buwanekabahu V (1357-1374 A.D.), Rajasingha I (1554-1593 A.D.), Vimaladharmasuriya I (1590-1604 A.D.), Senarath (1604-1634 A.D.), Vimaladharmasuriya II (1687-1707 A.D.), and Sri Veera Parakrama Narendrasinha (1707-1739 A.D.) contributed to restore and rehabilitate the cave temple (State of Conservation Report, 2019). The Dambulu Vihara Tudapata given by King Sri Veera Parakrama Narendrasingha in 1726 A.D. (this is a copy of a land grant to the Dambulla Viharaya certified by Narendrasingha) reveals the history and other details of the Dambulla Viharaya including the descriptions of the statues, the lineage of monks who looked after the temple, and contribution of the other kings who involved in the development of the temple (Seneviratna, 1983). According to the Dambulu Vihara Tudapata of King Kirti Sri Rajasingha [(1747-1782 A.D.) this is also a copy of a land grant made to the Dambulla Viharaya by Rajasingha in 1780 A.D.], the entire temple complex was restored and refurbished under the direction of the king (Abeyawardana, 2004; State of Conservation Report, 2019).

Modern period

In 1815, the Kingdom of Kandy (the last kingdom of Sri Lanka) was annexed to the British throne. and as a result of that, the temple lost its patronages received from the royals. However, Dambulla continuously existed as an important religious and political centre among the locals during this period. The Matale rebellion that took place in 1848 against the British colonial government has links with the Dambulla temple. As a part of this rebellion, on the night of 26th July 1848, a pretender named Gongalegoda Banda (alias Peliyagoda David) accompanied by Puran Appu (alias Francisku) and Dingirala was crowned at the Dambulla temple as the King of Kandy by Giranagama Thera (Seneviratna, 1983).

The temple is described in detail by several foreign writers such as John Davy (An Account of the Interior of Ceylon, and of Its Inhabitants: With Travels in that Island, 1821), J. Forbes (Eleven years in Ceylon, 1840), J.E. Tennent (Ceylon, 1859), S.M. Burrows (Buried cities of Ceylon, 1885), A.C. Lawrie (Gazetteer of the Central Province of Ceylon, 1896), and H.W. Cave [(Ruined cities of Ceylon, 1900) Seneviratna, 1983; Wickremasinghe, 1912].

In the 18th century, major development processes were carried out on the temple complex. During this period, the upper terrace was restored and

all the painted cave surfaces were painted or over-painted in a style

characteristic of the Kandyan school of the late 18th century (State of

Conservation Report, 2019). Also, the fronting screen walls were rebuilt

and roofs were added to the caves to form an outer verandah. In 1915, the caves were entirely repainted with the help of a local donor named Tolambagolle Korala of Ehelepola (Seneviratna, 1983; State of Conservation Report, 2019). In the 1930s, the verandah facades were constructed with the guidance of the then-custodian monk of the temple (State of Conservation Report, 2019).

The temple

Rangiri Dambulla cave temple is located in Dambulla, a small town positioned at the centre of the triangle formed by the three ancient capitals of Sri Lanka: viz; Anuradhapura, Polonnaruwa, and Kandy (Seneviratna, 1983). The Dambulla rock which has been formed by the combination of two rock outcrops separated by a narrow pass is located at a height of 168 m above the mean sea level and rises up to a height of about 180 m (State of Conservation Report, 2019). The cave shrines are situated more than halfway up on the southern slope of the Dambulla rock. Nearly 90 cave shelters, mainly scattered in two clusters, have been

identified at the southern and western parts of the Dambulla rock (State

of Conservation Report, 2019). The ancient Sigiriya Palace, another World Heritage Site in the country, and the famous Alu Viharaya temple are also situated near the Dambulla cave temple.

Presently, the temple is controlled by the Mahanayaka of Asgiri Maha Viharaya (Seneviratna, 1983; State of Conservation Report, 2019).

The Cave Shrines

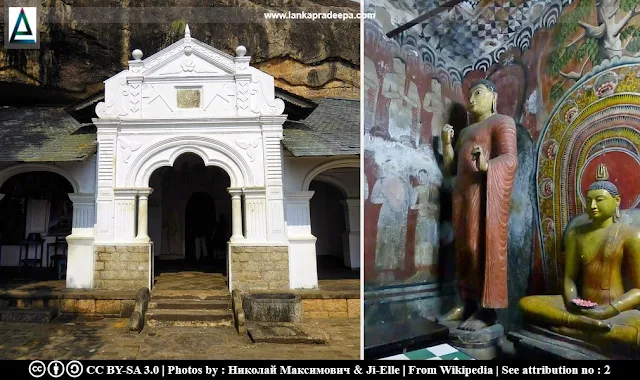

The complex comprises five separate chambers/caves partitioned by brick walls. In front of these five caves is a single verandah facing the south. The five caves have been numbered from 1 to 5 from the east to west and the common frontal compound of these cave shrines can be accessed through an entrance hall or doorway known as Vahalkada of recent date.

Totally 157 statues are found in all five cave shrines and

many of them are older than the murals (State of Conservation Report,

2019). The Buddhist mural paintings are of particular importance, as are

the

157 statues. The paintings in the five caves cover an area of about

2,100 m2. This is the largest extent covered by Buddhist paintings found in the country in a single Vihara (Abeyawardana, 2004).

The majority of paintings seen today are works of the kings of the latter part of the Kandyan Kingdom, mainly of the 17th and 18th centuries (Seneviratna, 1983). The paintings are said to have been done by Nilagama Sittara Paramparawa [(artists of the generation of Nilagama) Seneviratna, 1983].

Cave No. 1: Devarajalena (the Cave of the Divine King)

The first cave located immediate vicinity of the Vahalkada (or the gateway) is known as the Devarajalena. It is a small cave when compared to the size of other caves. A colossal reclining Buddha statue depicting Parinibbana Manchaka (Buddha in his final passing away) is the main object of worship in this cave. This statue has been carved out of the living rock and coated with paint. A statue of Ananda Thera is found at the feet of this statue and three seated statues of Buddha and a statue of Visnu are found near the head of it. Another statue of Buddha is found near its feet. Traditionally all these seven statues are attributed to King Valagambha's period but on the artistic features they possess, these statues have been dated by scholars to a much later period.

There is a Visnu Devalaya attached to this cave shrine from the outside. The statue of this Devalaya, according to popular belief, is the same statue that was originally at Devinuwara Visnu Devalaya (Seneviratna, 1983). It is also said that this statue was kept at Alut Nuwara Devalaya and Maha Saman Devalaya before it was finally taken to Dambulla Viharaya (Seneviratna, 1983).

Cave No. 2: Maharajalena (the Cave of the Great King)

This cave is known as Maharajalena because of the presence of the statues of Kings Valagamba and Nissankamalla (Seneviratna, 1983). The cave is 122 ft long, 75 ft wide, and 21 ft high near the front wall (Seneviratna, 1983). It is considered the most artistically important cave among the others as it contains the largest number of sculptures as well as many impressive paintings drawn on the cave walls and the ceiling.

There are nearly sixty statues in the cave (Seneviratna, 1983). Among them, a large number of Buddha statues in the seated, lying, and standing postures are found. Statues of the four gods namely Natha, Maitreya, Upulvan, and Saman and the statues of the Kings Valagamba and Nissankamalla are also found (Jayasuriya, 2016; Seneviratna, 1983). These statues are made out of either brick, stucco granite or wood (Seneviratna, 1983).

King Valagamba

This statue is made of wood and has been painted over. The right hand of the statue is in the Vitarka Mudra while the left hand is in the Varada Mudra (Seneviratna, 1983). The upper body is bare and a Makuta (a head-dress) is found on the head.

King Nissankamalla

As in the statue of King Valagamba, the right hand of this statue depicts Vitarka Mudra. The left hand rests on the waist of the body slightly inclined towards the right side. The upper body is bare but ornamented with jewellery such as necklaces, bangles, etc.

The standing Buddha under the Makara Thorana

This statue of Buddha is the main statue of the cave and is in the standing posture under a Makara Thorana (a dragon arch). The right hand of the statue depicts the Abhaya Mudra while the left hand shows the ring-hand attitude holding the uplifted hem of the robe. The statue has been painted over but the gold colour patches of the old paint are still visible. Therefore, some believe that this could be one of the statues supposed to have been gilded by King Nissankamalla (Seneviratna, 1983). The statue has some similar features that are found on the statues of the Anuradhapura Period such as the Standing Buddha Statues at Ruwanweliseya (Seneviratna, 1983).

The statue is accompanied by the images of Mahayana Bodhisattvas, Maitreya on the left, and Natha on the right. This pair of Bodhisattvas is considered unique because Dambulla is only the place where these two characters are found standing together in the sculptured form (Seneviratna, 1983).

The Stupa

The small painted Stupa in the Maharajalena is surrounded by eleven seated Buddha statues (Seneviratna, 1983). Two of them are represented with the snake king Muchalinda, who sheltered the Buddha during the sixth week after he attained the Buddhahood.

Murals

A large number of paintings are found drawn on the walls and ceiling of this cave. The paintings mainly depict special incidents related to the early history of Buddhism, to the history of Sri Lanka as well as to the life of the Buddha (Seneviratna, 1983). Scenes depicting the story of Mahindagamanaya (the arrival of Mahinda Thera the son of the Emperor Asoka, who together with other Buddhist monks brought the Buddhist teaching to Sri Lanka), Dumindagamanaya (the arrival of Sangamitta Theri the Buddhist nun who brought the sapling of Sri Maha Bodhi to Sri Lanka), the war between King Dutugemunu (161-137 B.C.) and Elara (205-161 B.C.), Suvisi Vivaranaya (24 assurances predicting Buddha-hood), life incidents of Prince Siddhartha, the struggle of Mara, attaining Buddhahood, Parinirvana (the final passing away) of the Buddha, are found among the paintings. The portraits of the gods Vibhishana, Skanda, and Ganesa are also found (Seneviratna, 1983). The patches that are found at several places in the paintings reveal that these paintings have been done over old paintings (Seneviratna, 1983).

The bowl

A bowl placed within an enclosure to collect the holy water that

drips through a fissure in the overhanging ceiling of the rock is found in this cave (State of

Conservation Report, 2019). Buddhist pilgrims believe that the drops of water falling into this bowl never stop even during a severe drought (Seneviratna, 1983). The water is used in daily temple rituals (Jayasuriya, 2016).

Cave No. 3: Maha Alut Viharaya (the New Great Temple)

This cave was converted to the present Buddhist shrine by King Kirti Sri Rajasinghe (1747-1782 A.D.) on the advice and guidance of Potuhera Ratanapala Thera, the then Mahanayaka (the chief monk) of Asgiri Maha Viharaya in Kandy (Seneviratna, 1983). Detail about its construction is available in Dambulu Vihara Tudapata of 1780 A.D., given by King Kirti Sri Rajasinghe (Seneviratna, 1983).

The cave is 90 ft long, 81 ft wide, and 36 ft high near the front wall (Seneviratna, 1983). Two entrances decorated with Makara Thorana (dragon arch) have been provided to enter into it. Dambulu Vihara Tudapata of 1780 A.D. reveals that King Kirti Sri Rajasinghe built a colossal reclining Buddha of about 30 ft long (Seneviratna, 1983). A seated Buddha under a Makara Thorana has also been built by him in the middle of the cave (Seneviratna, 1983). Presently, this statue is surrounded by fifty-seven statues and of them, fifteen are seated statues while the remaining forty-two are standing posture (Seneviratna, 1983). A statue of King Kirti Sri Rajasinghe is also found here.

Cave No. 4: Pacchima Viharaya (the Western Temple)

This cave is 54 ft long, 27 ft wide, and 27 ft high near the front wall (Seneviratna, 1983). A seated statue of Buddha under a Makara Thorana is the main object of worship here. A painted small Stupa is also in the middle of the cave. This Stupa is known as the Soma-cetiya because of the local belief that it contains the jewellery of Somawathi, the queen of King Valagamba (Seneviratna, 1983). In the mid-1980s, the Stupa was broken by

thieves to rob treasures believed to have been enshrined inside its dome

(Seneviratna, 1983; State of Conservation Report, 2019).

Cave No. 5: Devana Alut Viharaya (the Second New Temple)

No proper detail is available about the establishment of this cave (Seneviratna, 1983). It was a storehouse before being converted into a cave shrine (Seneviratna, 1983). Eleven Buddha statues including one colossal reclining statue, five seated statues, and five standing statues are found in this cave. Images of gods such as Visnu, Kataragama, and Devatha Bandara are also found (Seneviratna, 1983).

It is believed that this is a work of the 19th century (Abeyawardana, 2004). The legend written on the wall of this shrine reveals that it was renovated in 1915 by a nobleman named Tolambagolla Korala of Uda Walawwa, Ehelepola (Seneviratna, 1983; State of Conservation Report, 2019).

A colossal gold-plated seated Buddha statue was established near the Kandy-Jaffna main road with other components such as a museum, shrine room, and pilgrims' rest. Presently, this compound is popularly known among the people as the Rangiridambulu Uyanwatta Viharaya (Abeyawardana, 2004).

A protected site

The ancient Dambulla cave temple situated in the Divisional Secretary’s Division of Dambulla is an archaeological protected site, declared by a

government gazette notification published on 30 August 1957. The area surrounding the Golden Temple of Dambulla is a sacred area as declared by the gazette notification published on 16 April 1981.

Attribution

2) Rock Cave Temple, Dambulla, Sri Lanka - panoramio (2) by Николай Максимович and Dambulla-First Cave (5) by Ji-Elle are licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

3) King Nissanka Malla by Sujeewads and Dambulla höhlentempel 2017-10-18 (18) by Z thomas are licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 & CC BY-SA 4.0

4) Dambulla, Sri Lanka - panoramio (86) by Daibo Taku and Dambulla-buddhastupa by Lankapic are licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 5) Dambulla cave temple 35 by Cherubino and LK-dambulla-cave-temple-inside-10 by Balou46 are licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

References

1) Abeyawardana, H.A.P., 2004. Heritage of Kandurata: Major natural,

cultural and historic sites. Colombo: The Central Bank of Sri Lanka.

pp.306-309.

2) Bandaranayake, S., 1997. The Dambulla rock temple complex, Sri Lanka. Agnew (1997), pp.46-55.

3) Jayasuriya, E., 2016. A guide to the Cultural Triangle of Sri Lanka. Central Cultural Fund. ISBN: 978-955-613-312-7. pp.100-107.

4) Paranavitana, S., 1970. Inscriptions of Ceylon: Volume I: Early Brahmi Inscriptions. Department of Archaeology Ceylon. pp.64-66.

5) Seneviratna, A., 1983. Golden Rock Temple of Dambulla; Caves of infinite Buddhas. UNESCO-Sri Lanka Cultural Triangle Project. Central Cultural Fund. Ministry of Cultural Affairs, Sri Lanka. pp.11,14,18,21-23,27-28,30-33,40-45,49-62,65-66.

6) State of Conservation Report, 2019. Golden Temple of Dambulla (Sri Lanka) (C 561). Department of Archaeology; Central Cultural Fund; Ministry of Housing, Construction and Cultural affairs; The Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka. pp.2-3,19, 21-37,69.

7) The Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka. No: 1164. 30 August 1957.

8) The Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka. No. 137. 16 April 1981.

9) Wickremasinghe, D.M.D.Z., 1912. Epigraphia Zeylanica: Being lithic and other inscription of Ceylon (Vol. I). London. Archaeological Survey of Ceylon. pp.121-135.

2) Bandaranayake, S., 1997. The Dambulla rock temple complex, Sri Lanka. Agnew (1997), pp.46-55.

3) Jayasuriya, E., 2016. A guide to the Cultural Triangle of Sri Lanka. Central Cultural Fund. ISBN: 978-955-613-312-7. pp.100-107.

4) Paranavitana, S., 1970. Inscriptions of Ceylon: Volume I: Early Brahmi Inscriptions. Department of Archaeology Ceylon. pp.64-66.

5) Seneviratna, A., 1983. Golden Rock Temple of Dambulla; Caves of infinite Buddhas. UNESCO-Sri Lanka Cultural Triangle Project. Central Cultural Fund. Ministry of Cultural Affairs, Sri Lanka. pp.11,14,18,21-23,27-28,30-33,40-45,49-62,65-66.

6) State of Conservation Report, 2019. Golden Temple of Dambulla (Sri Lanka) (C 561). Department of Archaeology; Central Cultural Fund; Ministry of Housing, Construction and Cultural affairs; The Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka. pp.2-3,19, 21-37,69.

7) The Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka. No: 1164. 30 August 1957.

8) The Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka. No. 137. 16 April 1981.

9) Wickremasinghe, D.M.D.Z., 1912. Epigraphia Zeylanica: Being lithic and other inscription of Ceylon (Vol. I). London. Archaeological Survey of Ceylon. pp.121-135.

Explore Other Nearby Attractions

Location Map (Google)

This page was last updated on 12 December 2023